One advantage of GiGL’s not-for-profit business model is that we are able to make selected information available for research projects, and Dr Sarah Knight is one of the incredible researchers we’ve had the privilege to work with. An ESRC Postdoctoral Fellow at the Environment and Geography department, University of York, she also leads the ESRC-funded Green & Gender-just Cities project. Her research explores the relationship between people and nature, and her recent study used GiGL datasets to investigate the link between ecological quality and Londoner’s well-being.

Natural environments, such as parks, rivers, and woodlands are known to be beneficial for our well-being. This is particularly important in cities, such as London, where people experience higher levels of pollution and population densities, and poorer mental health. In fact, London’s parks & open spaces are estimated to save the city £950 million in health care costs a year (Heritage Fund).

However, little is known about how the ecological quality of these natural environments affects our well-being. The ecological quality of a site depends on its biological, physical, and chemical conditions, and not all spaces are equal! For London, Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) are recognised as being of particular importance to wildlife and diversity, so can be used to represent sites of high ecological quality.

In our recent paper, my colleagues at York and I asked if the presence of significant habitat for wildlife and biodiversity in urban green and blue spaces was important for the well-being of Londoners. We used survey data about people from the Understanding Society project, linked with data from Greenspace Information for Greater London CIC (GiGL), to find out if living far away from London’s SINCs was bad for well-being.

The answer was yes!

Why is this important?

- Londoners’ life satisfaction and feelings of self-worth are lower than the national average (Thrive LDN),

- Londoners have 18.96 m2 of greenspace provision per person, almost half the national average (Fields in Trust),

- SINCs support 91% of the protected species in Greater London and nearly all of the city’s Biodiversity Action Plan priority species (London Wildlife Trust’s Spaces Wild), but biodiversity levels are declining.

How did we use the data?

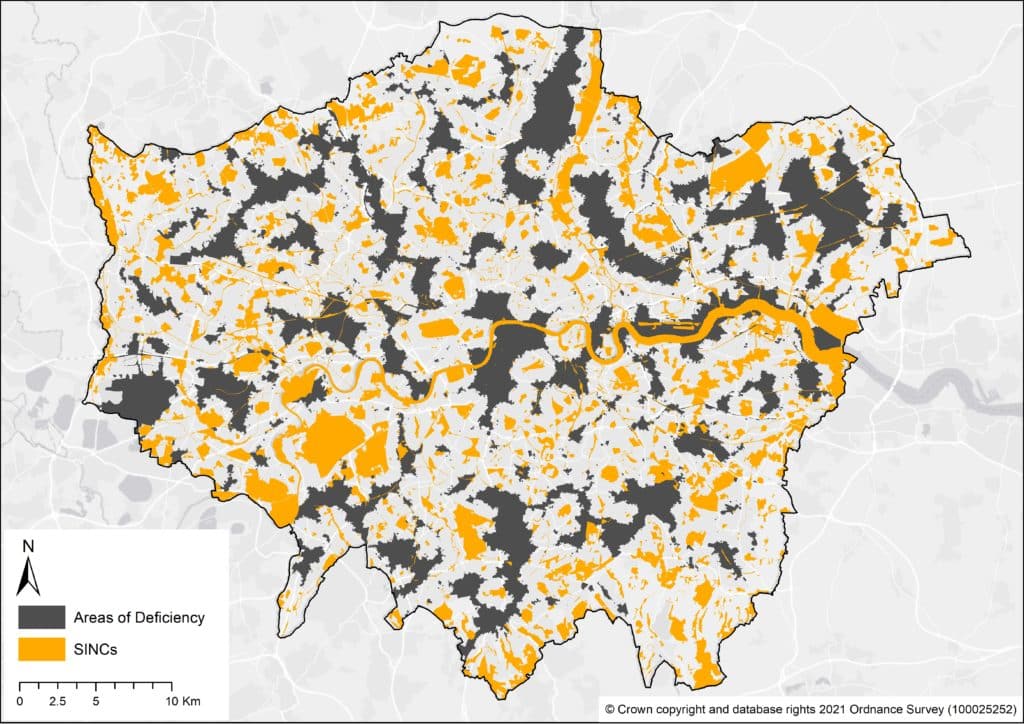

We used the Areas of Deficiency in Access to Nature (SINC AoD) dataset modelled by GiGL to identify parts of the city that had poor access to nature. GiGL defines this as ‘Areas where people have to walk more than one kilometre to reach an accessible SINC of Metropolitan or Borough Importance’. The AoD mapping is a sophisticated approach, using network analysis tools to model walking distances along actual routes from known entry points to each SINC. This provides a highly accurate way of identifying locations that lack access to high-quality nature in the city.

We then linked this to the residential locations of adults in Greater London from the large, multi-year British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). The BHPS ran from 1991-2008 and contains information on individuals including their postcode, which allowed us to identify if a person lived in an AoD, and measures of self-reported well-being. By creating a dataset that tracked every participant in the sample for up to 18 years, we were able to examine how living in deficiency to nature was associated with changes in their level of well-being.

We used two well-being measures from the BHPS: life satisfaction and mental distress (the General Health Questionnaire, GHQ). Because well-being is also determined by many things, we controlled for factors such as people’s income, marital and employment status, and age, and for area factors including neighbourhood deprivation and air pollution. For comparison, we repeated the exact same analysis using GiGL’s Deficiency in Access to Public Open Space datasets, to account for all public green and blue spaces irrespective of their ecological quality.

What we found

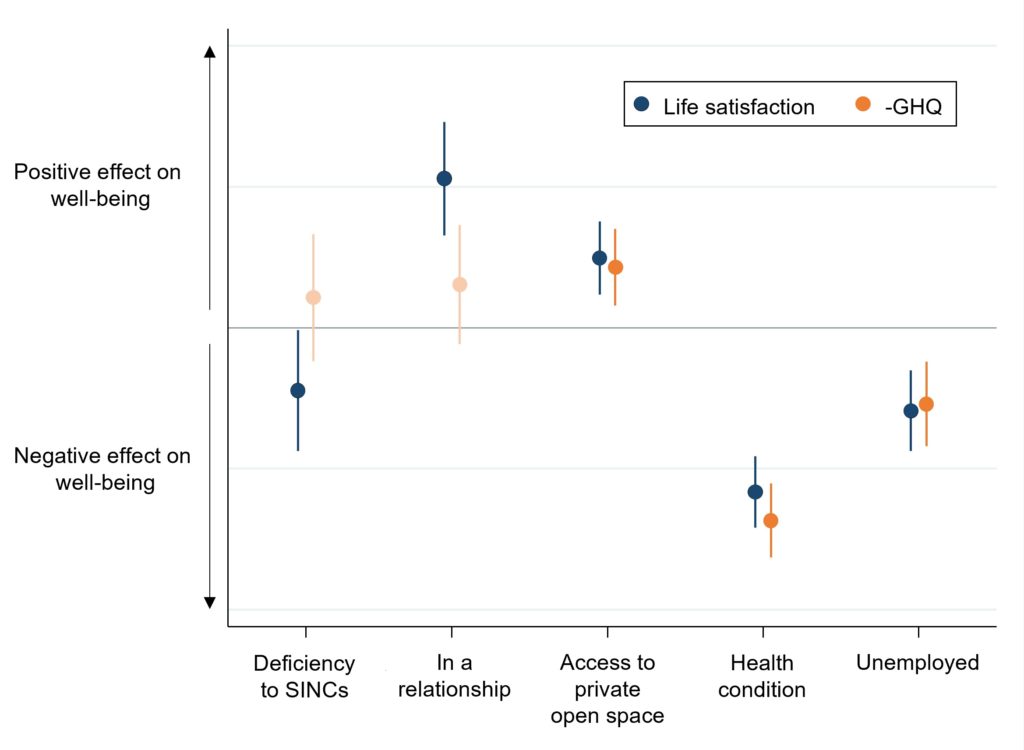

Our first key finding was that life satisfaction is lower for people living in places that are deficient in access to nature. This suggests that the ecological quality of the natural environment is an important factor for well-being in London.

So why is this? It might be that more biodiverse environments provide opportunities for restoration or ‘soft’ distraction, such as noticing habitats or birds, as opposed to ‘hard’ distraction such as car noise and traffic lights. Alternatively, it might be that places of higher or important biodiversity, particularly in urban areas, are seen as special, rare, or different. This makes sense in highly urbanised areas, where opportunities to connect to nature are few.

Our second finding was that there is no relationship between mental distress (GHQ) and deficiency in access to nature. This finding compliments other research that suggests nature exposure has a stronger effect on positive emotions, such as life satisfaction, rather than negative ones, such as mental distress. Well-being is a complex phenomenon to measure, and it is likely that different aspects respond to nature exposure in various different ways.

Finally, our third finding was that there was no relationship between either measure of well-being and access to Public Open Spaces. This suggests that the ecological quality of green and blue spaces, rather than provision alone, is important for well-being!

Next steps

“There are opportunities to improve health through the choices government, regulators, businesses and individuals make in creating and contributing to healthier, greener and more accessible environments” – Environment Agency.

Our findings are important because they demonstrate the potential benefits of conserving existing natural spaces and developing new high quality ones in deficient areas for both the environmental and our well-being. They also show that the SINC network is not only important for London’s nature, but also for individual well-being in the city.

This study has a number of key improvements on previous work, such as the use of highly detailed green and blue space information from GiGL and access to individual well-being records over long periods of time. However, many questions remain! Does high ecological quality directly impact well-being (so is a causal relationship), or do some individuals with higher self-reported well-being choose to live closer to high quality natural sites? What specific biodiversity factors are important for well-being? How can we ensure the benefits derived from access to green and blue spaces are distributed fairly? Through continued collaboration with GiGL, I am attempting to answer these questions by analysing large amounts of data across the capital using GiGL’s data products.

You can read the original paper here and follow Sarah on Twitter @sarah_gis.

This looks like an excellent study, correcting as it does for most other factors that could affect well-being and mental health. I had not realised before that there might be such wide differences between mental health and feelings of well-being from access to nature. The quality of the area of deficiency data pays off in such work. All credit to Ian Yarham for taking this forward and GIGL for carrying it on.

Just two caveats in this. The work is correlative and so suggestive, rather than proof of, cause and effect. There can be local studies that are below par for which GIGL takes on the results uncritically. A gross example local to me is an entirely fictional Area of Deficiency centered on the Grade II* heritage Wimbledon Park. This is being used by both LB Merton and the All England Lawn Tennis Club to miss-represent opportunities here. Erroneous data lead to a perception that we have priority here. We don’t!

Extra access to nature here is a luxury and would be a welcome luxury, but the error should not enter into statisitics tracking change in access to nature.

I was interested to see the map of Areas of Deficiency and how close it is to the original map that I drew up some 18 years ago when I worked for the GLA. Over a few years I visited every site in London, mapping access points to where ‘hands on’ nature could be accessed. The Borough Grade 1 Norwood Cemetery was a good example where the Area of Deficiency bordered the cemetery because there was only one entrance on the far side. It is difficult to see from the scale of the map what has changed but the major one I think I can see is the opening up of Walthamstow Wetlands.