Planning has a very important part to play in helping to protect and restore London’s natural environment. Under the Environment Act 2021, from November 2023 all appropriate developments will have to deliver a minimum of 10% biodiversity net gain (BNG) using Defra’s BNG metric. Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) also have a strengthened legal duty to conserve and enhance biodiversity, alongside new biodiversity reporting requirements, such as providing summaries of how BNG obligations have been met.

BNG does not replace or weaken any other protection for biodiversity or processes that are already in place (e.g. protected species legislation, ecological impact appraisals, etc.). The mitigation hierarchy (avoid, mitigate, compensate) still applies; first avoid harm to biodiversity, then minimise adverse impacts on biodiversity and only as a last resort compensate for losses that cannot be avoided. For more information see “Biodiversity net gain. Good practice principles for development. A practical guide.” 2019.

GiGL has been supporting our partners in their BNG preparation since 2018 and we have been involved in various projects and discussions promoting the importance of using a robust evidence base in the BNG process. You can visit our BNG webpage for more information on the projects GiGL are working on and our BNG resources page for a compilation of resources.

In this article we will focus on our BNG pilot projects which we have been working on with a few of our Service Level Agreement (SLA) partner LPAs.

| BNG metric | A biodiversity accounting tool that uses habitat features to assess an area’s biodiversity value for the purpose of BNG. It can be used by any development project, consenting body or landowner that needs to calculate biodiversity losses and gains for terrestrial and/or intertidal habitats. |

| BNG distinctiveness | A measure based on the type of habitat and its distinguishing features. This includes consideration of species richness, rarity, the extent to which the habitat is protected by designations and the degree to which a habitat supports species rarely found in other habitats. The metric automatically assigns a distinctiveness category based on habitat type. |

| BNG condition | A measure of a habitat against its ecological optimum state. Condition is a way of measuring variation in the quality of habitat parcels of the same habitat type. |

| BNG strategic significance | The local significance of a habitat based on its location and habitat type. Higher scoring locations and habitats can be determined in the Local Plan, strategies and policies of each LPA. |

The London Borough (LB) of Sutton has been at the forefront of BNG preparations in London. Since 2018, they have set up their own biodiversity offsetting mechanism with a bespoke biodiversity offsetting metric (more information on Sutton’s work here and here). Since LB Sutton has been a long term GiGL SLA partner, it was only natural to start working with them on our BNG pilot project.

We started the work with Sutton’s biodiversity team in summer 2022 and through their expertise and useful inputs refined our methodology for these pilot projects. In February/March 2023, we started working with 3 more LPAs (LB Southwark, LB Camden and LB Bexley) as we were keen to expand the pilots to other areas that would likely have different requirements. We are also about to start working on a fifth pilot project with LB Bromley and are in discussion with another borough who is keen to work with us.

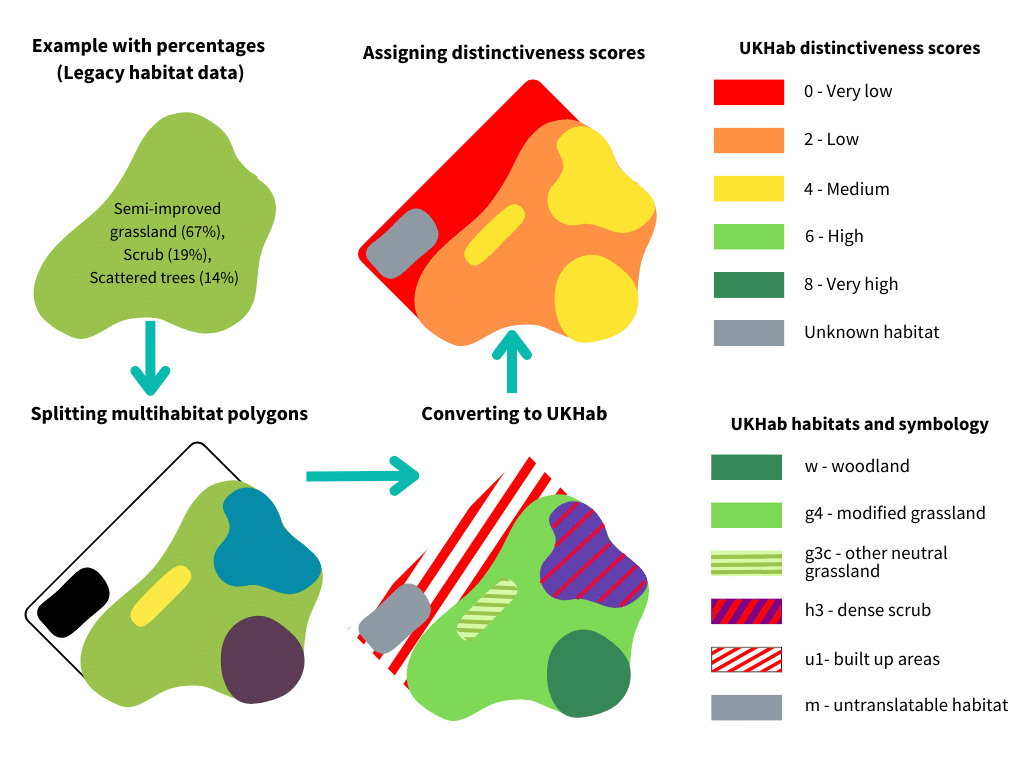

So, what are these BNG pilot projects about? The aim of the project is to create a BNG baseline for each area that can be used as an indication of its biodiversity value. Since BNG is a habitat based approach, this baseline is created using GiGL’s legacy habitat dataset, Ordnance Survey Master Map (OSMM) and where available more recent site survey data. The image below shows an illustrative example of the process of getting from multi-habitat parcels (legacy habitat dataset) to single habitat polygons, converting the habitats using the UKHab classification system (the habitat classification system used predominantly in BNG) and using the BNG metric to assign habitat distinctiveness scores. It shows an ideal scenario if data at the appropriate scale are available. If you’d like more information on the process of converting our legacy habitat data to UKHab please read this GiGLer article.

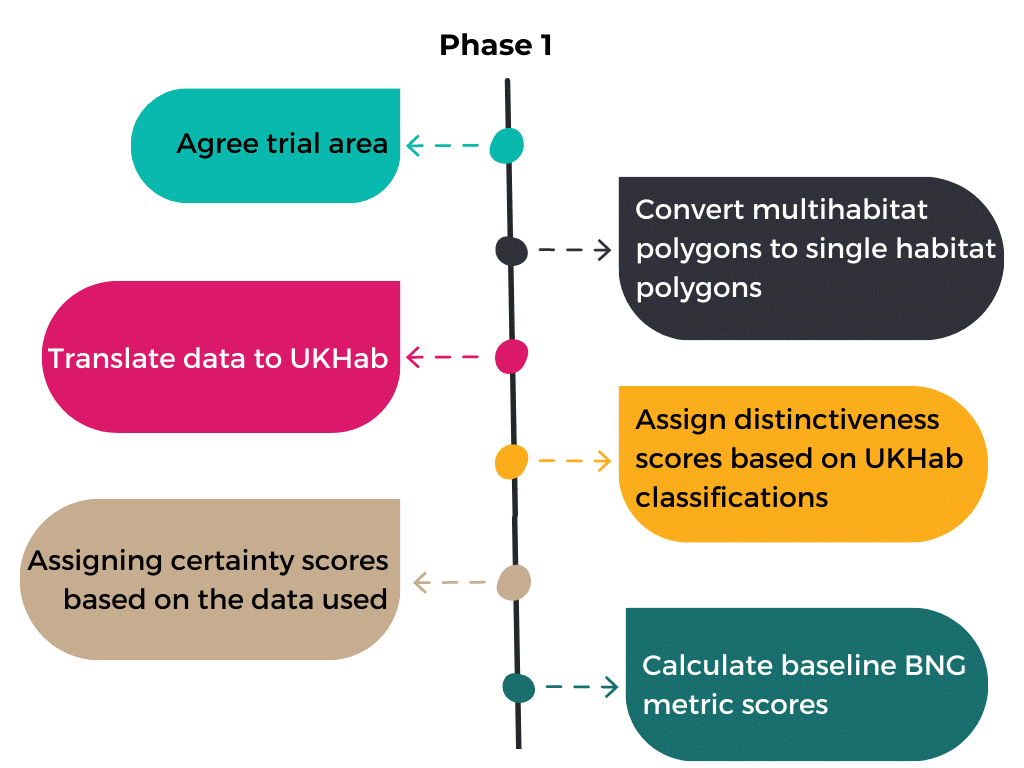

We have split the BNG pilot projects into two phases. For phase 1 we work on a smaller trial area of the borough. We ideally prefer an area where there is a mix of habitats and land-use types in order to fully test our methodology and outputs. Once we have agreed a trial area we proceed with the process described above of converting the multi-habitat polygons to single-habitat polygons and then translating the data to UKHab. Using the BNG metric classifications we then assign distinctiveness scores based on the habitats we have identified in each polygon. We also assign certainty scores based on the data we have used to arrive to the conclusion that a certain polygon has a specific habitat type. For example, our certainty is higher for the polygons we have recent data on from full habitat surveys.

We can then calculate the BNG baseline metric scores for the trial area. For this purpose however we use default values for the condition and strategic significance scores, which are inputs that are required in the BNG metric in order to calculate the biodiversity units. These are defined in the table above and more information can be found in The Biodiversity Metric 4.0 User Guide. We will be able to use more accurate values to calculate these scores once we have more information from LPAs on the strategic significance of areas and habitats, as well as more up-to-date data from surveys that have carried out condition assessments.

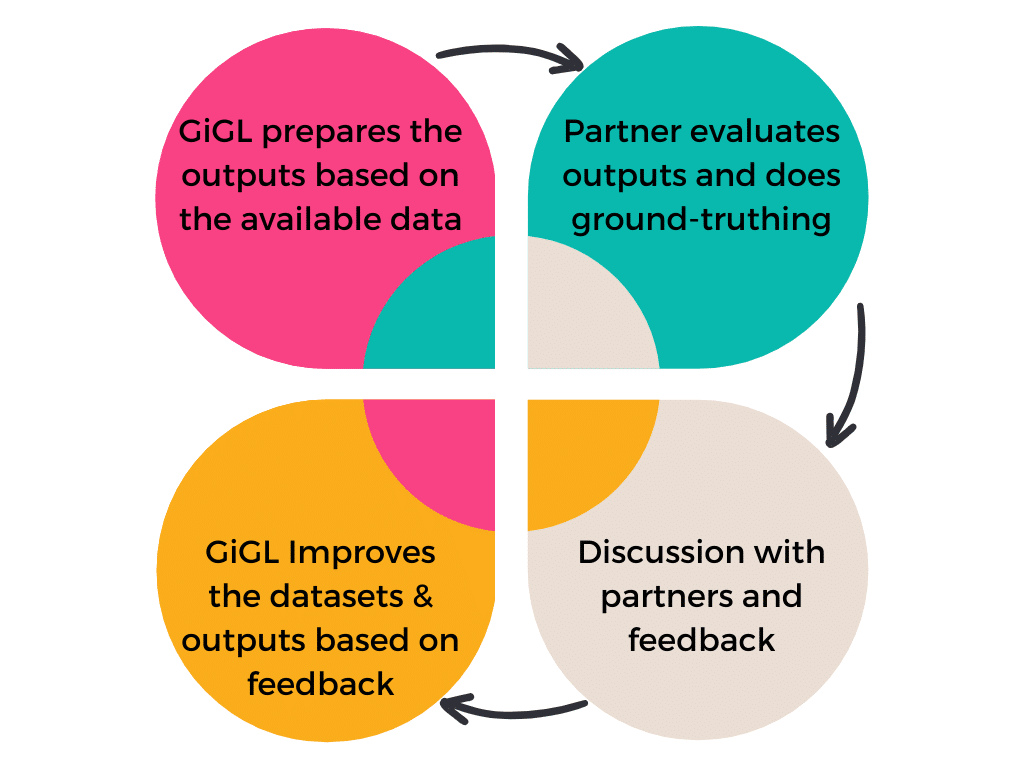

Once all this work is complete we send GIS files and detailed PDF maps to our BNG pilot partners. They then investigate these outputs based on their knowledge of their local area and potentially identify areas they would like to do ground-truthing. These can be areas where habitat data might not appear very accurate or show the whole picture or areas of unknown habitats. The partners then send their feedback back to us and any new appropriate data. The GiGL team then works on the feedback to update the outputs accordingly and send them back to them. Throughout the process we also have meetings with our partners to discuss the methodology and any feedback.

We have delivered phase 1 to all our initial BNG pilots and we are currently working on feedback we have received and incorporating any new habitat data. The GiGL team is gearing up to deliver phase 2 ahead of November’s deadline when BNG will become mandatory for new developments. Phase 2 involves expanding all the steps outlined above to the whole LPA.

It has been a great experience working with our partners on this project and we have definitely learnt a lot. The BNG process is quite complex and GiGL is keen to support our SLA partners and clients with BNG requirements. The outputs produced from this project can be used as a high level baseline and to assist discussions at a borough level. They could also be used by LPAs as part of their evidence base when reviewing their Local Plans to inform borough-specific BNG policies. At the granular level of specific development projects we believe that these data can help with providing an indication of the potential habitats present but on-site assessments are necessary for more granular data and site specific calculations. There are limitations and we are working to refine the process, and as more up-to-date data come in the more accurate the baseline will be.

I’ve been looking at a big planning application local to me, where a net gain is claimed. In fact, there’ll be a net loss.

It’s a remnant of an 18th C park with old trees in a grassland matrix, self-established alkaline-soil woodlands, wet woodland, reedbed, shallow eutrophic lake, with European Eel. the site has 8 species of bat and good numbers of swifts. it’s a Site of Borough Importance, grade I. As a multiple-use urban site it is already good and difficult to improve.

The applicant identifies priorities: veteran trees and reedbed and dismisses all the rest. Protecting existing veterans is no gain, especially when the grassland matrix is sacrificed to development. Wet woodland isn’t even identified. Existing reedbeds are ignored and new ones are proposed. The lake needs desilting, but the proposed method would pollute it seriously.

Gain requires the existing baseline to be quantified, but the applicant didn’t look hard enough and so undervalued all but the veteran trees. Take this together with unrealistic projections for the future and the use of the calculator is invalidated: rubbish-in, rubbish-out. The calculator makes this deception opaque.

So, beware. Clever use of the right machine serves to obscure inadequate survey, failure to identify habitat components correctly, or at all and overoptimistic promises.

My view is that the net gain calculator merely serves to hide to distortions.