Where ideas shared are problems halved

We are delighted to feature an article from Ann Davidson of the London Geodiversity Partnership, sharing her delight for and insight into the earth beneath our feet. Since 2012, GiGL have collaborated with LGP to share geodiversity data to ensure sites of geological importance are protected for everyone to enjoy. In this article, Ann shares some of her favourite sites which encapsulate the diversity of geology London has to offer.

I have often been asked, “What is geology – that’s all about rocks, isn’t it?”, or “It’s about dinosaurs, isn’t it?”, but geology is so much more.

Of course, rocks and fossils do feature in most lists of geological topics, but the list is likely to also contain the following:

- Building materials

- Climate change and weather extremes

- Communications

- Contamination

- Earth’s origin and place in the solar system

- Energy

- Extraction of minerals used for practically everything…

- Food production

- Geomorphology

- Hazardous processes etc.

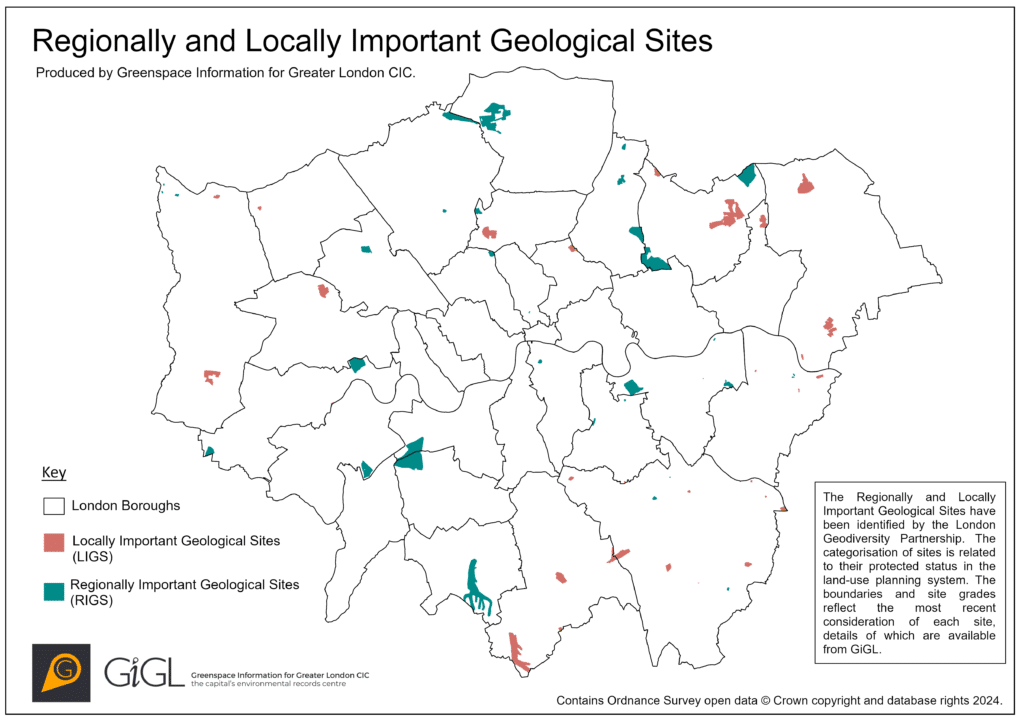

The aim of the London Geodiversity Partnership (LGP) is to identify, conserve, and make available to researchers and interested members of the public, the most important sites of geological interest in Greater London. The list includes Geotrails and Bus Pass Geology Routes and, at least one site of geological interest in each London Borough – graded at either a Local or Regional level, depending upon importance. Sites first need to be identified and researched, a few need regular conservation, and all sites are reviewed every five years to check the accuracy of the online citations. Many sites also have interesting stories to tell, about their cultural and industrial history. The raw data of each site is stored within the London Geodiversity Sites database, hosted by GiGL in collaboration with LGP, making geodiversity data available to whoever necessary to confer protection of the sites and their history. By sharing the site citations freely, LGP helps anyone to unearth the intrigue beneath their feet.

Getting to know an area well can be a little like reading a good book. One becomes drawn into the story as more facts are revealed, and it is satisfying to piece them together to make sense of it all. However, the end of the story sometimes poses as many questions as it answers. There’s a wealth of information available from geological maps and books, old and new, and of course from LGP members and partners.

As geology is a multidisciplinary subject, it is good that LGP is a means to link groups as varied as GiGL, the Amateur Geological Society, and Historic England, which all have interests of considerable overlap. LGP partners can learn and benefit from sharing their particular interests and observations.

Although comprising just one species on Earth, humans are dominant in so many areas, but we all rely on the world’s limited resources to survive, so it is vital that we study and respect other species. The authors of my favourite geology book assert that Earth processes influence human lives daily, and human influence changes the Earth of the future. I love this about geology. It is always relevant to our lives and our surroundings, because everything you see is related to geology in some way.

The Earth is around 4.54 billion years old, plus or minus about 50 million years. That’s a lot of geology to contend with, hence new theories abound as research methods are refined. However, for LGP, generally the first thing to be done is to visit a new site or walk a new trail, then determine the points of most interest, and make them and their history accessible to other people. LGP’s work helps to show how geology shapes lives today.

A current discussion in geology circles concerns the age and origins of Stanmore Gravel, found at the geological Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) at Harrow Weald Common (GLA18, London Borough Harrow). Having been challenged to study the problem at their local site, Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society members are currently trying to reach a consensus and bring the project to a conclusion. As is often the case with research, this may or may not satisfy all concerned, but their painstaking process, like GiGL’s painstaking data collection, will make a difference to future theories.

Although a tiny area on the Earth, London’s geology is relatively diverse. A lot of sites could be described as chalky or watery, most of them show geology in situ, but some relate to rocks brought from other parts of the UK or overseas.

Below is a very brief description of a few LGP sites. To learn more about these sites and others, visit the LGP web pages.

GLA – Greater London Authority

SGI – Site of Geological Interest

Chalk-related sites:

GLA 26, Riddlesdown Quarry, London Borough of Croydon:

The site, formerly known as The Rose and Crown Chalk Pit, is possibly the most important geological site in London. The spectacular cliff is visible from the airfield at Kenley across the valley. Conservation is also needed here to clear undergrowth from access routes and the cliff-face. Annual working days at the Quarry might be hard work but are also enjoyable.

The site has exposures of three chalk formations, and is valuable as a safe place for research and education. Groups, including school parties, can pre-arrange to visit the quarry. See Itinerary 9 in the Geologists’ Association Guide No. 68, compiled by Diana Clements.

GLA 34, Harefield Pit, London Borough of Hillingdon:

Different animals feature here. A recent conservation day, at this former chalk pit, was a long-awaited event. For several years, access to clear thick undergrowth from the cliff-face had been denied because of the presence of badger setts in the immediate area. Permission was finally given after a long wait, as monitoring found no recent evidence of badger activity. This small but steep cliff shows burrows (coloured by glauconitic sand against the white of the chalk) from the Upnor Formation, descending into the chalk. The burrows are thought to have been made by a shrimp-like crustacean, Glyphicnus Harefieldensis, named after the site. This clearance of the exposure was successful but will probably become an annual event.

One hopes that the badgers found a better home somewhere!

Water-related sites:

GLA 39, Erith Submerged Forest, London Borough of Bexley:

If you carefully follow all safety advice when visiting Erith Submerged Forest, and go on the foreshore at a falling tide, you will see stumps and roots of trees from 3,000 to 5,000 years ago. This site signals a change from drier to wetter atmospheric conditions with trees such as yew and water-loving alder co-occurring.

SGI 18, Bow Creek Meanders, London Boroughs of Newham and Tower Hamlets:

Bow Creek meanders show a smaller but more prominent feature than the more well-known meanders around the Isle of Dogs. They relate to a lower gradient of the river bed, where the river’s lower energy can no longer cut a straight channel. These meanders are best seen from the Docklands Light Railway, but even better from the air!

GLA 48, Thames Foreshore, London Borough of Hounslow:

The Thames Foreshore at Isleworth, on a low tide, exposes small patches of London Clay with plant and animal fossils, the most commonly found being tube worms.

Artworks:

SGI 19, City of London Cemetery, London Borough of Newham:

This is London’s largest Cemetery, with avenues of trees and a variety of wildlife. The geological interest in most cemeteries is the types of stone used to mark the graves and their different patterns and rates of erosion.

Sites which are seen daily by many residents, and visitors to London, include SGI 7, Memorial to the Siege of Malta, City of London. This stone was brought from Malta, to be in keeping with the commemoration of the George Cross Islanders. Visit the site at Tower Hill. SGI 6, University College Hospital, London Borough of Camden is another unobtrusive yet interesting geological artwork. This is a colourful, polished, conglomerate boulder from Brazil. It was designed to be used as seating and is at the main entrance to UCH.

Another geo-artwork is SGI 24, ‘Walking the Dog’, (Peter Randall-Page), London Borough of Southwark. It is composed of three glacial erratics, with a continuous raised track around each boulder. Sometimes, after long periods of rain and with a magnifier, it is possible to see the exquisite, brilliant green mosses that grow in the carved gullies.

Former Industrial Sites:

Many sites in London have an industrial past, the industries having grown from using the materials found locally. As the capital’s population increased rapidly, so did the number of brickworks, providing bricks for houses, schools and factories. The best bricks were made from brickearth or Claygate Formation, small areas of which remain today, on hilltops above the London Clay. Although there were brickworks all over London in the mid-nineteenth century, there is little trace of them now. Some pits were infilled and some left undulating topography. There is a brick and tile ‘bottle’ kiln at SGI 15, Walmer Lane, London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, and a lime kiln, SGI 22, Burgess Park, London Borough of Southwark. The Burgess kiln is located in what was once a thriving industrial area of the city on the bank of the Grand Surrey Canal, before the canal was filled over the 20th century.

The canal was built to transport goods and materials to and from Surrey Docks. Evidence of brickworks can be found where black, clinker bricks, over-baked in the centre of a kiln, have been used to build garden walls. This is strikingly obvious in Willesden Green, where most of the front gardens in nine or ten nearby roads, are enclosed by walls made from clinker bricks. See SGI 4, Grange Brick and Tile Works, London Borough of Brent.

Large park sites such as Waterlow and Greenwich have several geological features such as far-reaching views, spring lines small pits and an observatory… Oh, and if it is only fossils that interest you, try the Essex Mammoth or Crystal Palace!

After describing these sites, the conclusion seems to be that the work carried out by GiGL and LGP has less in common than have the sites themselves. If, through our collaboration, geologists learn more about biodiversity and GiGLers learn more about geodiversity, perhaps we will all find more things to enthuse us. To end on a hopeful note, long may biodiversity and geodiversity co-exist.

To come along to geoconservation days and learn more about London’s varied geodiversity, check out LGP’s upcoming events here.

Every time I cycle to work to Highgate I curse the Bagshot Sands – that last steep climb to the top of the hill s a killer. You can pretty much map the outcrop just from the change in gradient. And our school Groundsmen just love the spring-line between the sand and the london clay beneath which makes some of the grounds a swamp in the winter.

If you would like to learn more about these sites and the work of the London Geodiversity Partnership, please contact

info@londongeopartnership.org.uk.

Thank you for the interesting article Ann, what is the favourite geology book that you mention?

Hi Tanvi,

Ann has let us know her favourite Geology book is this: Environmental Geology by Barbara W. Murck, Brian J. Skinner and Stephen C. Porter, Published by John Wiley & Sons Inc.