Over the last few months, I have been testing other recording apps, to provide a thorough overview of all that is available to newer recorders or those interested in testing new ways of storing and sharing their data. iNaturalist (featured in the previous article) provides all the exciting software and connection to global community science initiatives needed to get a beginner addicted to biological recording, but for some contexts, it is insufficient.

- If you can submit only single occurrence records at a time, how can you accurately map the spread of the invasive floating pennywort creeping for 10s of metres across a canal?

- Or if there is no function to easily share a measure of survey effort, how can you share ‘non-detection’ records for more accurate representations of species’ distributions?

- And how confidently can you identify a bird species if you can only hear its call, without being able to observe the animal?

The value and results of structured surveys performed by species experts cannot be replicated by taxonomic novices with an app, but where experts can’t reach or can’t regularly repeat monitoring, an army of enthusiastic Community Scientists armed with accessible and reliable tools, can really help plug gaps in recording. By understanding the differences in how to use the different tools and their respective limitations, this army can also help to limit false identifications and duplications.

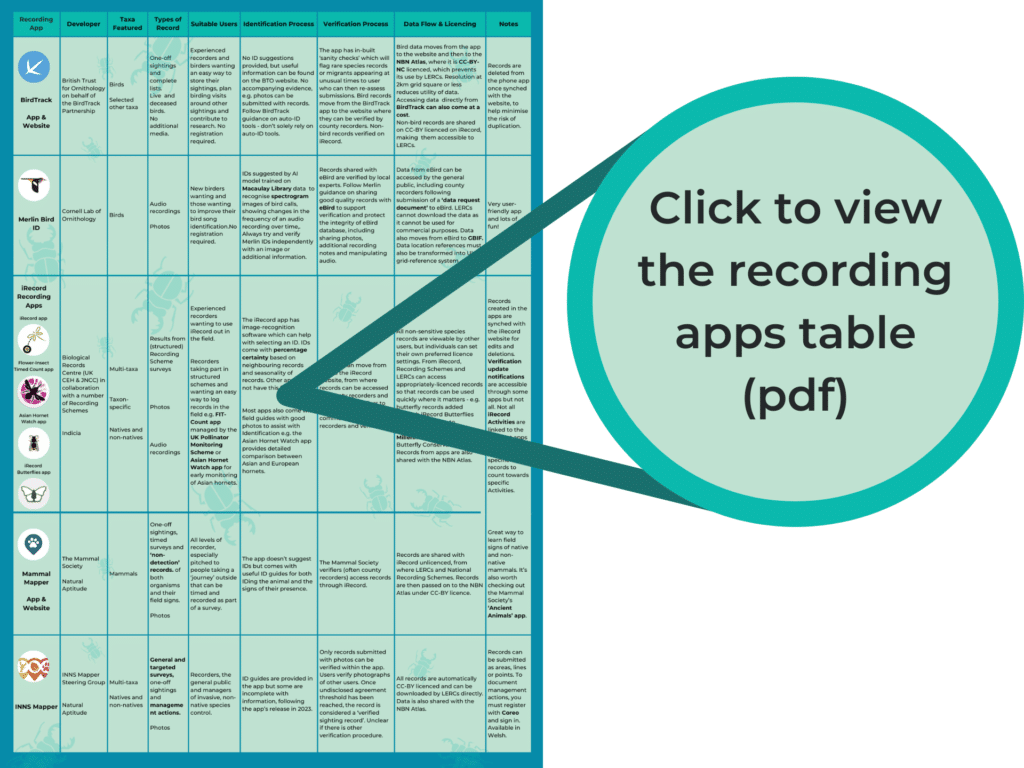

Within this article, I have opted to only explore apps which are both focused on a specific biological group, and also share data with accessible data warehouses. There are certainly others which do and don’t meet these criteria, and if you have a favourite deserving of some praise, please share it in the comments or by engaging with our social media.

Check out the table here, and at the end of the article, for the full comparison.

The Birds, the birds!

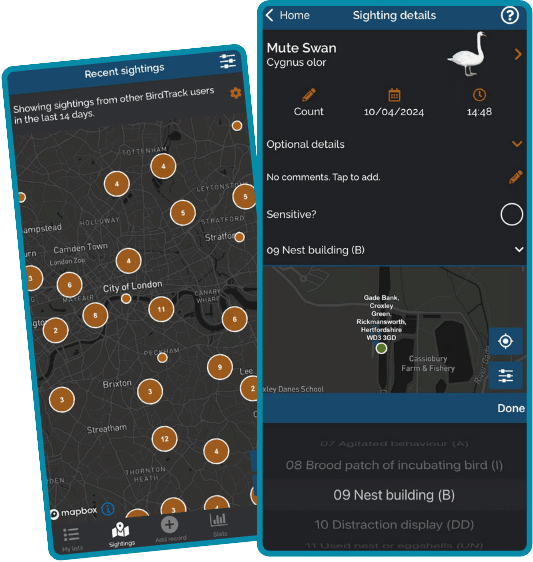

Birders are prolific biological recorders, capturing their work in life lists and avidly investigating what their neighbouring birders have been seeing, hearing and inferring. BirdTrack, developed by the British Trust for Ornithologists on behalf of the BirdTrack Partnership in 2004 enables the collation of one-off records, species lists and deceased bird records, as well as the ability to view others’ records in the surrounding area. It is the app of choice for many birders and provides such reliable data that it is used extensively in research and conservation.

BirdTrack is a great way to both store your data and to help you collect specific details that provide a more accurate reflection of bird populations, their phenology and the threat of avian flu, for example, the direction of flight, breeding plumage details, and reporting of dead birds.

Bird records and lists are shared from BirdTrack to the NBN Atlas at a low resolution and licenced as CC-BY-NC, making them inaccessible for use by LERCs. Since 2022 the records of the select few non-bird taxa which can be recorded through the app (amphibians, butterflies, mammals, dragonflies, plants and reptiles) are sent to iRecord for verification. From iRecord, the non-bird data are available to all, being CC-BY licenced. This does not apply to bird records.

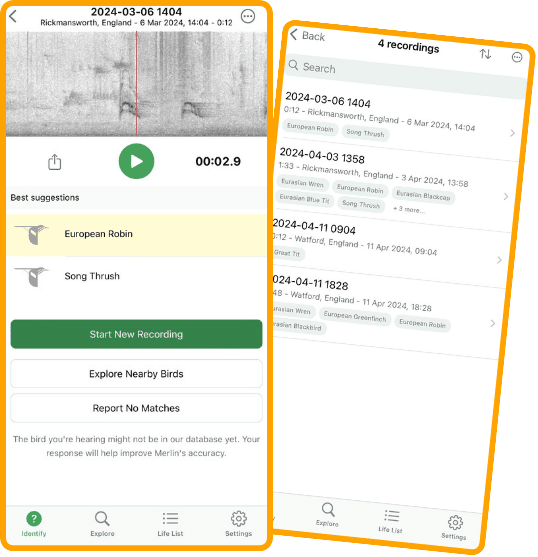

One of the joys of bird watching is being able to listen closely to, as well as observe, the world around us. Developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology who also manage eBird, The Merlin Bird ID app helps to transform the twittering and whistling soundscape into distinct, identified bird calls.

From a live recording taken with just a phone microphone, the audio data are converted into a visual spectrogram, showing the variation of sound wave frequencies produced over time. Pre-defined spectrograms are already a common tool for birders to identify a species from its call, but the Merlin app takes this a step further by suggesting IDs of all the birds featured within a recording, in real-time. Using a computer vision model like that employed by iNaturalist, the Merlin model has been trained on the spectrograms and images in the vast Macauley Library to learn which components of a spectrogram are likely to correspond to the species you are hearing. Paired with regional information on bird distributions, downloaded in the form of ‘packs’ and useable offline, Merlin IDs for common species have been pleasantly surprising birders.

As both Merlin and the Macauley Library are managed by the Cornell lab, users are encouraged to ‘archive’ their audio data and records to the library to grow the model’s training data and increase the accuracy of identification predictions. The information within eBird is also used within extensive scientific research – just scrolling through the publications page of the eBird website gives an idea of the huge potential of eBird data.

When sharing records or lists from the Merlin app with eBird, it is strongly recommended to follow the eBird guidance – ensuring that records are submitted with audio recordings featuring a single species, that accompanying evidence like photos are provided and that the Merlin ID suggestions are interrogated using other sources of information. This all helps eBird reviewers to verify an increasing number of records more easily and minimises the need for further querying. Following the guidance also helps to maintain the integrity of the eBird data source which would otherwise suffer with misidentifications or records lacking in evidence. The app is obviously not foolproof, with users noting that it struggles with quiet calls and high levels of background noise. Further issues arise from identifying different types of call from the same species, similar calls from different species, mimics and even regional dialects. Even if you don’t feel confident in using Merlin for making records, there is something truly magical about watching the invisible but vocal diversity dance across your screen. It’s great for getting started with learning bird calls but be careful in using it on its own for sharing records of rarer species.

Spot the field signs!

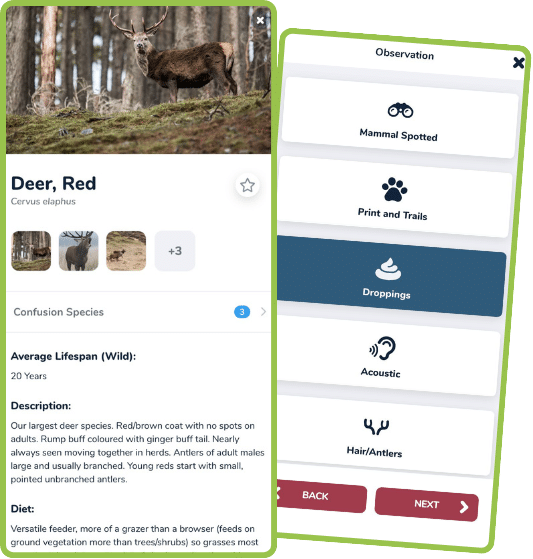

Another taxon-specific app which has gained popularity is Mammal Mapper from the Mammal Society, available as both an app and website. Many UK mammals are hard to spot being skittish, nocturnal, tiny or all three, so being able to accurately assess and identify their field signs is vital to recording them. While field guides are perfect for this, you never know when you might come across a mysterious poo or surprising paw-print to which you might want the answer, ‘who left this?’.

Mammal mapper helps to identify tracks/trails, droppings, feeding signs dens/burrows and other signs of activity (as well as actual sightings) of native and non-native species with easy to use and clear ID guides integrated into the app. Typical species range maps also help to confirm the identity of the field signer. The app also has the option of submitting a survey rather than individual record by recording a timed journey tracked through GPS during which sightings or a lack thereof can be reported. This measure of survey effort helps to validate ‘non-detection’ records which are just as important for understanding a species’ distribution.

Data from the app are passed from Coreo, an online database, to the Indicia data warehouse and can be linked to iRecord, for verifying by experts at 100m resolution. Records are licenced under a CC-BY licence meaning that from iRecord, LERCs, the NBN Atlas and others can access the data.

Record your efforts

As with some of the apps above, understanding the ‘effort’ that went into a species record – how much time was spent looking, how many surveys were completed etc., can help record users understand the true distribution and population size of a species. This is especially important when dealing with invasive non-native species to be able to effectively monitor their spread.

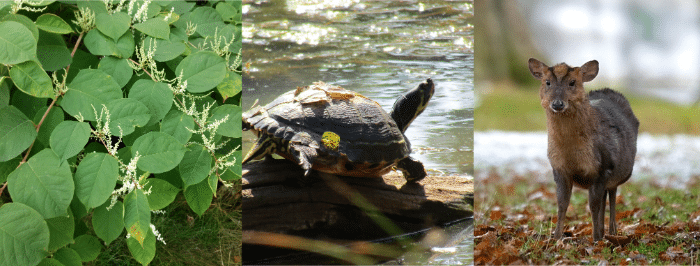

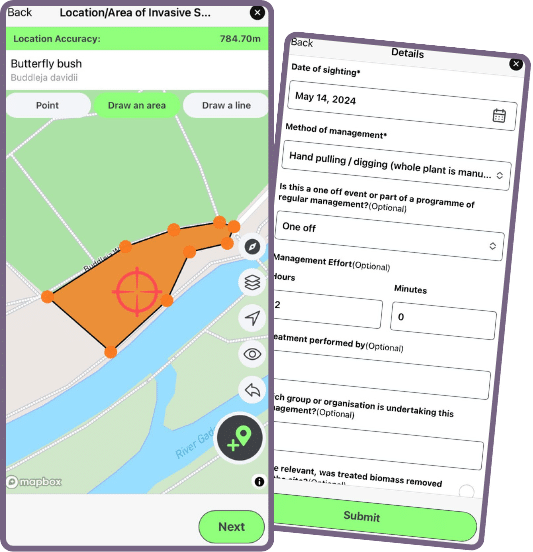

Launched last year as a collaboration between the Yorkshire and North Wales Wildlife Trusts, the Invasive and Non-Native Species Mapper app, allows recorders to record two different types of survey – general and targeted. Much like the Mammal Mapper surveys, the app pinpoints your location using GPS and follows you as you move about an area. If you come across one of the 62 freshwater and terrestrial invasive species featured in the app during your survey, you pin the location and make a record. The app will continue to monitor and time your movements until you ‘finish the survey’.

Completing targeted surveys creates valid, non-detection records which can be extremely useful when trying to assess the efficacy of management actions, which can also be documented in the app.

In a recent webinar, The Yorkshire Wildlife Trust shared how they have used both features to great effect when coordinating management actions of different groups to control invasive plant species across the Colne and Calder catchments. Accurate reporting of the spread of the invasives (as a point, line or area) helped target management actions and by noting the interventions in the app, standardised information was shared easily between all staff and volunteers. It also helped to signal to members of the public that invasive species management was a priority and actively occurring around them. All records are CC-BY licenced allowing LERCs to also access the data for their area – this is enhanced by being able to filter records by LERC area. Data are also shared with the NBN Atlas.

Like iNaturalist and unlike the other apps discussed in this article, other users can contribute to the verification process by verifying photos. It is unclear at what level of community agreement, a photo has been considered correctly identified. This is also somewhat hampered by some incomplete ID guides at the time of writing.

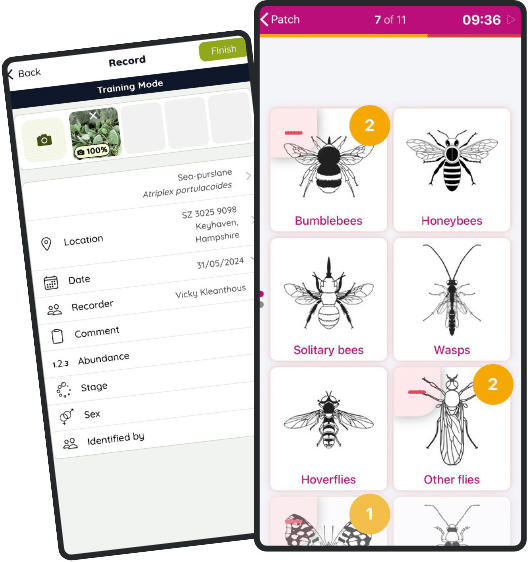

The original and beloved iRecord has also created a range of survey-specific apps which are compatible with the community science methodologies created and employed by the UK’s Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and Biological Records Centre. One such example is the Flower-Insect Timed Count (FIT Count) app. The app will take you through how to complete a 10-minute survey counting the number of flowers and their insect visitors in a 50cm2 patch. Following the standardised method again gives an indication of recording effort, which is key to accurately assessing the decline of insect populations around the world.

All iRecord app records can be synched with the iRecord website so that users can view all of their records in one place – be aware that not all verification notifications or updates can be viewed through the apps.

You can view a full list of all apps developed by the Biological Records Centre here.

As the inexhaustive list above shows, there is truly a recording app for all needs – whether you want to improve identifying field signs or monitor invasive species, you can make a start on your phone. While I will never tire of extolling the engagement potential of using recording apps, if you want your records to be of high, verifiable quality and to contribute to wider research and conservation, there are some key things to be aware of:

- Know where data are shared and who can access the information – data can only move through a data flow pathway if they are appropriately licenced (CC0 or CC-BY) so make sure to check your settings.

- Avoid duplicating your data by understanding the data flow pathway associated with the app. If you want to share data directly with GiGL, let us know where else you are submitting data. If you do share data in multiple places which are already linked, keep all the information consistent – especially coordinate resolution.

- Never take an app’s identification at face-value – do your own investigations, trust the experts and the data that they have generated.

- Provide as much evidence as you can – don’t rely on a single source.

- Use the forums – the forums for different apps are full of tips on making the most of the app and to share their limitations.

- Try to avoid being fatigued by all the choice – if you’ve found one thing that you like and meets your needs in terms of accurate identifications, level of engagement with other users and wider contributions, then stick to it! There’s no harm in trialling other apps but don’t let the choice overwhelm you.

- Don’t forget the nature! Don’t let your desire to document the natural world let you forget just how extraordinary it can be to experience it. Gamification is a great tool for engagement but it shouldn’t come at the expense of the organism welfare or the condition of its habitat.

Swiftmapper.org.uk

for recording the location of Swift nests, nesting boxes or ‘screaming parties’ (=groups of Swifts flying at roof level and using screaming calls to identify their nesting sites.)

Vert useful and comprehensive article. It introduced me to some new recording apps and has explained the advantages and disadvantages of others. In the future, perhaps all the apps will share data with one another and with GiGL etc