At GiGL, we have been working since 2018 to support our stakeholders with the then emerging biodiversity net gain (BNG) scheme. In 2021, BNG was part of the Environment Act (2021) and therefore not a voluntary scheme anymore (once the transitional period had passed). Hence in recent years, we have been working more closely with our stakeholders to figure out the best way to support them with the new BNG requirements. We carried out a series of BNG pilot projects (read more about them here), formed a BNG advisory group (more on that later), have been exploring new BNG services and have been asking for inputs in meetings, interactive sessions and questionnaire surveys.

You can learn more about our work in relation to BNG in our webpage here. If you’d like some further reading, we have compiled some external resources on BNG here. If you’re not familiar with BNG, here are some definitions and further information.

BNG became mandatory for major developments on 12th February 2024 (with a few exemptions), and for small sites on 2nd April 2024 (exemptions apply here too). It will become mandatory for nationally significant infrastructure projects in November 2025.

Biodiversity net gain: “Biodiversity net gain (BNG) is a way of creating and improving natural habitats. BNG makes sure development has a measurably positive impact (‘net gain’) on biodiversity, compared to what was there before development. (…) Developers must deliver a BNG of 10%. This means a development will result in more or better quality natural habitat than there was before development.” (From Defra’s Biodiversity Net Gain Collections webpage, accessed 06/09/2024)

BNG metric: A biodiversity accounting tool that uses habitat features to assess an area’s biodiversity value for the purpose of BNG. It can be used by any development project, consenting body or landowner that needs to calculate biodiversity losses and gains for terrestrial and/or intertidal habitats.

BNG Strategic Significance: The local significance of a habitat based on its location and habitat type. Higher scoring locations and habitats can be determined in the Local Plan, strategies and policies of each Local Planning Authority prior to a Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) being published.

One of the services we’ve been exploring would involve mapping the areas of medium and high strategic significance for Greater London to help developers and ecological consultants find this information quickly and easily. This way we want to ensure that nature is taken into account in development, appropriate compensation measures (in the form of BNG units) are being proposed based on the available evidence and local knowledge, and that opportunities for nature recovery are not being lost due to the lack of clear information. This could be used in the interim until London’s Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) is published which will then form the basis for calculating strategic significance (see descriptions in the table below). The metric essentially penalises the removal of the relevant habitat and rewards the improvement or creation of these habitats.

Table 1: The different categories for strategic significance and their description where a Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) has not been published and where an LNRS has been published. The information is taken from the Statutory Biodiversity Metric User Guide (February 2024).

| Strategic significance category | Description where an LNRS has not been published | Description where an LNRS has been published |

|---|---|---|

| High | Formally identified in a local strategy. The habitat type is mapped and described as locally ecologically important within a specific location, within documents specified by the relevant planning authority. | This category can be applied when: 1) the location of the habitat parcel has been mapped in the Local Habitat Map as an area where a potential measure has been proposed to help deliver the priorities of that LNRS; and 2) the intervention is consistent with the potential measure proposed for that location. |

| Medium | Location ecologically desirable but not in local strategy. This category can be applied when the Local Planning Authority has not identified a suitable document for assessing strategic significance. | Not applicable. |

| Low | Area or compensation not in local strategy. Where the definitions for high or medium strategic significance are not met. | Where the definitions for high strategic significance are not met. |

We soon realised that it would take us longer than we thought to decide, coordinate and map these areas for all Local Authorities in London. By then, London’s LNRS would be published and the work obsolete. It was, however, a useful exercise with our stakeholders and we are thankful to all the people who provided their inputs and helped us in this process. We decided to publish this article to show our decision process and so people who are interested in this topic can find this information.

Other parts of the country have published interim guidance identifying these areas to help developers and their consultants incorporate the right strategic significance scores in the BNG metric. For example, Norwich[1], Doncaster[2] and Buckinghamshire[3] identified biodiversity opportunity/character areas and priority habitats within those areas, in addition to other ecologically desirable locations. Leicestershire and Rutland[4] outlined the process and relevant sites, areas and species in their guidance. But London is unique and complicated. With 32 boroughs, the City of London and two Mayoral Corporations forming the 35 Local Planning Authorities (LPAs), there are a lot of different approaches, Local Plans, Biodiversity Action Plans and other strategies to consider.

We tried working with Local Authority partners to examine if we could narrow down what should be included in the two strategic significance categories (medium and high) so we could use our data to map these areas. However, this was not as straightforward as we initially thought. Various considerations were put on the table:

- Should Local Plans have more weight than other documents (e.g. Biodiversity Action Plans)?

- Should buffer zones around designated sites be considered for medium strategic significance even though they are not covered in Plans and Strategies?

- What about green corridors and the instances that there are differences in the green corridors identified in Local Plans and other documents? Or when the methodology used to identify them is not clear?

We then turned to our BNG advisory group for inputs. This group is comprised of experts in their field, from a mix of our stakeholders who are actively involved in BNG. The membership includes a local authority ecologist, BNG officer and planner, ecological and sustainability consultants and representatives from the Greater London Authority, Transport for London, London Wildlife Trust and Natural England, with some members also being part of GiGL’s Board of Directors. In recent meetings, we’ve also had other invited attendees with expertise or interest in the topic of discussion. So, we asked these experts for their advice on what they think should be included in these two categories based on the published guidance and their experience. We received various responses:

High Strategic Significance

The consensus for this category was that it should include areas/habitats within Local Nature Reserves, Local Wildlife Sites (in London known as Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation or SINCs), green corridors from Local Plans and green corridors from other published local strategies.

Medium Strategic Significance

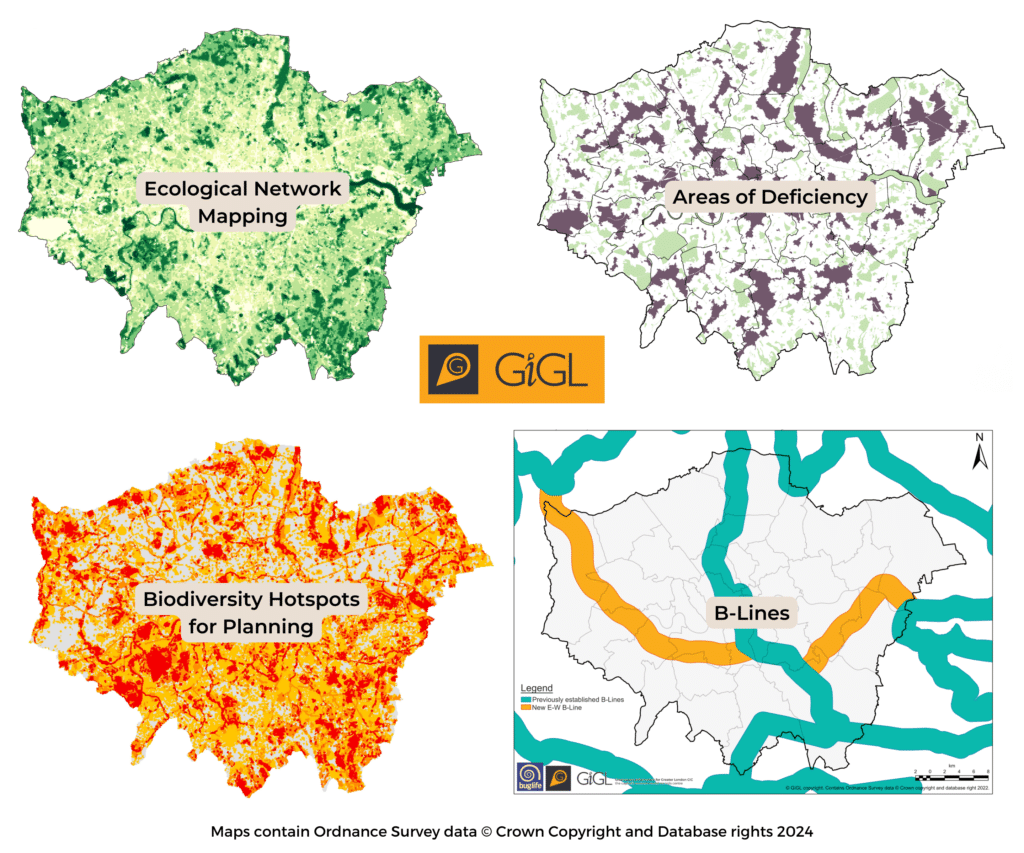

This category is more subjective as it refers to ecologically desirable areas that are not in local strategies. Ideas included proposed SINCs, locations outside the high strategic significance areas but within GiGL’s Ecological Network Mapping, Areas of Deficiency in Access to Nature, ecological functionality in the form of species/taxon strategic areas (e.g. B-Lines, Important Invertebrate Areas, etc.), and other species information.

Furthermore, the group discussed other important elements that should be considered too. For example, buffer zones around important areas such as SINCs. Green and open spaces that are not captured within the SINC network but can nonetheless have important habitats and act as stepping stones for wildlife. Other suggestions included habitat opportunity areas (e.g. woodland opportunity mapping), Natural England’s habitat network map (in MAGIC), GiGL’s Biodiversity Hotspots for Planning, key/priority habitats in Local Biodiversity Action Plans (or other local strategies) and the London Environment Strategy policies.

Sometimes work might not progress as we initially think it will, but along the way we learn, adapt and get ideas for other work. In the biodiversity conservation field, it’s important we share not only the successes but also the things that didn’t quite work as planned in order to improve methods and processes in the future. This is relevant to practical conservation interventions in situ, as well as computer based, policy and legislation applications.

[1] Norwich: BNG Planning Guidance Note & Biodiversity Baseline Study (February 2024)

[2] Doncaster: Planning Policy Guidance – Assigning Strategic Significance for applications subject to mandatory BNG (March 2024)

[3] Buckinghamshire: Interim Strategic Significance & Spatial Risk Guidance for Biodiversity Net Gain in Buckinghamshire Council’s Local Planning Authority Area (February 2023)

[4] Leicestershire and Rutland: Applying the Biodiversity Net-gain metric – Interim guidance for assessing strategic significance in Leicestershire and Rutland (March 2022)

I agree that there Biodiversity Net Gain is a great idea as a mechanism to overcome the death from a thousand cuts that is typical of weighing biodiversity in the planning balance which existed previously. However, I believe that it has many attributes of having been planned by a representative committee. The autumn free lecture series appended may be of interest to others who are struggling with the labirynthine statutory methodology.

Ecology and Conservation Studies Society

in conjunction with the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew.

Free Lecture Series 2024

Biodiversity net gain – What are the prospects?

31st Oct, Mike Waite, Director of Research & Monitoring · Surrey Wildlife Trust. Biodiversity Net Gain in the planning system.

14th Nov, Dave Dawson, Independent Environmental Scientist. Bitcoin biodiversity

21st Nov. Nick White, Principal Advisor – Net Gain, Natural England. Biodiversity Net Gain – what impact has the mandatory approach had?

All are welcome. These free lectures introduce cutting-edge practical ecology in-depth and in an accessible way. They not only give practitioners access to the latest science and practice, but also help to underpin the knowledge of everyone with a concern for our biodiversity.

The lectures will be held in the Lady Lisa Sainsbury Lecture Theatre, Jodrell Laboratory, Kew Gardens, TW9 3DS. Access is via the Jodrell Gate, Kew Road.

The gate will open at 17:30 and the lecture begins at 18:00, when the gate is closed, so no late entries. Discussion will end by 19:15 when the gate is re-opened, and the lecture theatre has to be empty by 19:30.

A voluntary collection will be made at the end to help the Society (ECSS) meet lecturers’ expenses.

Biodiversity Net Gain, what are the prospects? Free lecture series

When planning applications for development are considered, planning authorities have long been encouraged to seek a net gain for biodiversity. Then, in February 2024, gain became a significant planning issue with the introduction of a new requirement for a minimum 10% gain in most development proposals. Applicants have to use a statutory metric to measure the current biodiversity value of the site and to demonstrate there will be a gain on-site, if not off-site, or pay into a fund. A new market in Biodiversity “units” is developing.

We have tried to halt Biodiversity loss before. The 1992 Rio Earth Summit adopted Agenda 21 for sustainable development and the UK Local Agenda resulted in much work on species and habitats. Biodiversity Acton Plans were developed for the UK and for local authority areas, leading to the listing of priority habitats and species. Public authorities were given a Biodiversity Duty in 2007. Then the 2010 Lawton report, Making Space for Nature, sought better protection and management of our designated wildlife sites; the establishment of new Ecological Restoration Zones; and better protection of our non-designated wildlife sites. Planning guidance, however, failed to protect any more sites.

These measures haven’t reversed the long-term decline documented in the latest UK state of nature report: 151 historic extinctions, one in six species currently at risk and a 20% current average rate of decline across all species. Not all changes come under planning control, notably the management of agricultural land and forests, but many proposals do. In this light, the lectures ask what to expect from the new requirements for no net loss in planning proposals?

I read some online comments on BNG by ecologists using BNG in planning applications. The general tone is that BNG is being misused in that it is trying to squeeze too much “habitat improvement nto too little space. This means that any gain is not sustainable. Species need space and routes to expand and to exchange genetic information between populations.